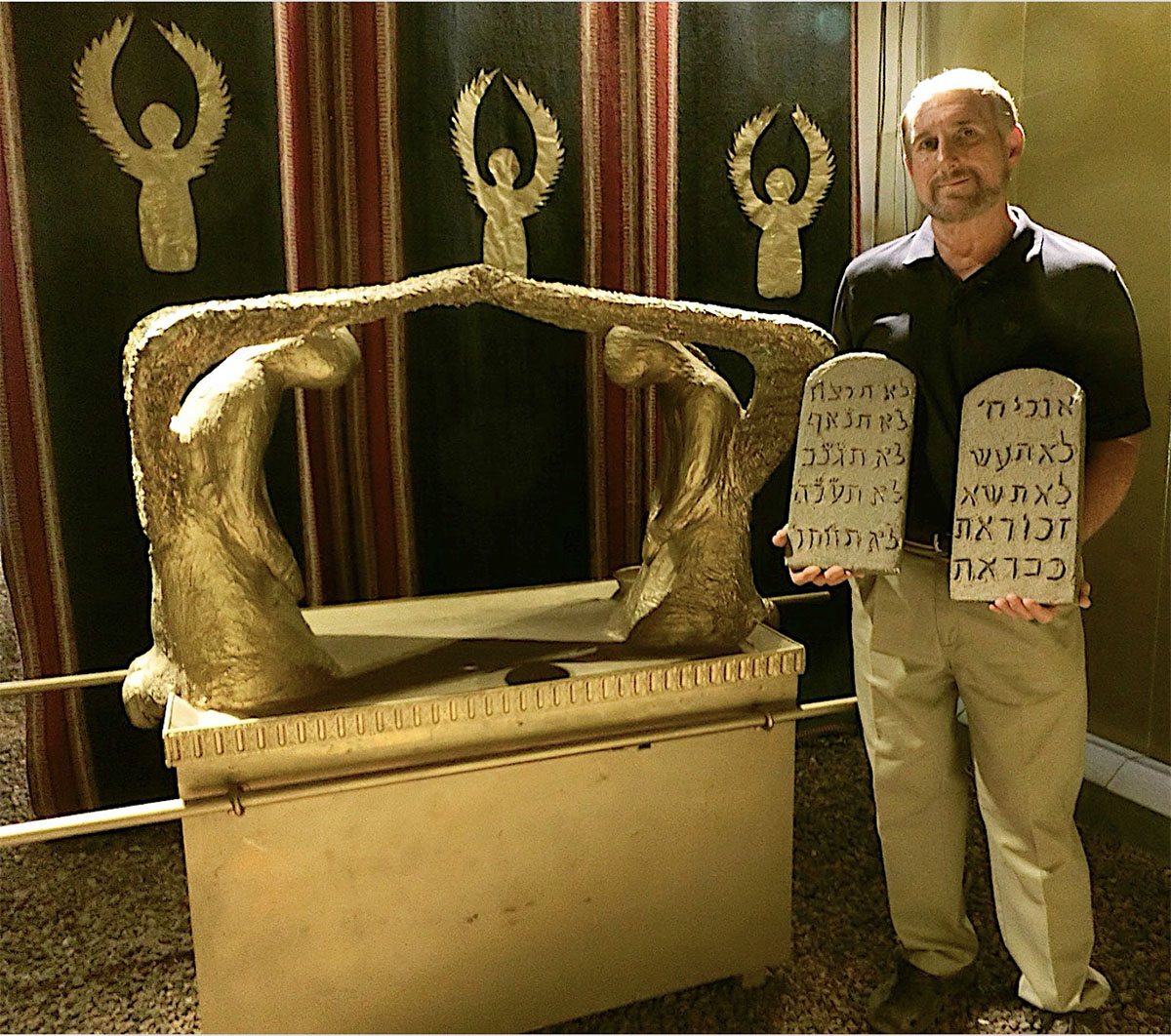

The Ark of the Covenant was largely introduced to people outside biblical circles through the Hollywood movie Raiders of the Lost Ark. Though the film was fantasy, it did place the Ark into an Egyptian setting, albeit in its supposed ancient hiding place. Students of the Bible know the Israelites built the Ark in the Sinai desert after fleeing Egypt, but it may come as a surprise to learn its style of construction also likely originated in Egypt.

Exodus 31:1–6 says the craftsmen Bezalel and Aholiab constructed the Ark. Since the Hebrews were coming from Egypt, it’s reasonable to assume they learned their craft there. The text says, “I [God] have put wisdom in the hearts of all the gifted artisans” (v. 6), meaning God enabled men already trained in the craft to follow His design for the Tabernacle and its furniture.

The statement implies making the objects would require both experience and divine guidance. Though the Ark was unique in its role as God’s footstool in the Tabernacle, it was comparable in design to similar objects from Egypt.

The Hebrew word for “ark” is aron and was also used for Egyptian coffins, such as that of Joseph (Gen. 50:26). The Egyptian sarcophagi of Osiris were adorned with a pair of winged figures like those above the Ark of the Covenant. The Egyptian treasures from the tomb of Tutankhamen provide examples of ark-like craftsmanship during the New Kingdom period (ca. 1567–1069 BC), when the Israelite Exodus and wilderness journey occurred.

Within Tutankhamen’s tomb were four gilded, wooden shrines that protected the Pharaoh’s mummified remains. In an arrangement resembling that of the Tabernacle, which contained the Ark inside the Holy of Holies inside the Tabernacle, the shrines fit one inside another. The innermost shrine was adorned on each side by cherub-like figures whose wings touched, a position similar to that of the two cherubim on the Ark (Ex. 25:20; 1 Ki. 8:7; 2 Chr. 5:8).

Moreover, another shrine, consisting of a rectangular wooden box overlaid with gold and equipped with carrying poles, resembles the biblical Ark that was made of acacia wood overlaid with gold (Ex. 25:11). The poles for this gilded chest of Tutankhamen had collars affixed at the inner ends so they could not be removed. The Bible explicitly says the Ark’s poles were not to be removed (v. 15). First Kings further records that the poles protruded through the curtain into the holy place, parallel to the Ark.

Tutankhamen’s golden chest also was similar in size to the box-shaped Ark that held the tablets of the Ten Commandments (Ex. 25:10). Like these Egyptian objects, Hebrews 9:4 indicates the Ark was covered on all sides with gold. King Solomon also used gold to overlay the interior of the first Temple (1 Ki. 6:21) and especially the two sculptured cherubim that overshadowed the Ark (v. 28).

The lid of the Ark (Hebrew, kapporet, “atonement piece”), called the “mercy seat,” was a separate piece of solid gold topped by the cherubim (Ex. 25:17–20). The mercy seat sat atop the Ark in the Tabernacle (v. 21; 26:34) and was where the high priest sprinkled the sacrificial blood on Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement). It was also here, between the cherubim, that the Divine Presence manifested itself (Ex. 25:22; Num. 7:89). Similarly, many of these burial objects of Tutankhamen were topped with an image of the god Anubis, symbolizing the assumed presence of this Egyptian deity.

These archaeological discoveries can help us gain a more realistic understanding of the Ark of the Covenant, which was at the center of Israel’s worship at the Tabernacle and first Temple and symbolized God’s restoration of a relationship with man after He exiled humanity from Eden (Gen. 3:24).